In 1971, in the midst of social struggles, La Classe Operaia Va in Paradiso (The Working Class Goes to Heaven) was released in Italian movie theaters. The film’s main character, Ludovico “Lulù” Massa, is a metallurgical worker, an advocate of piecework, supporting two families, and praised by his superiors for his fanatical productivity. One day, he loses a finger while working and realizes that none of his superiors care about his health conditions. He also becomes aware of the reality around him: his co-workers despise his agitation and servility toward the bosses. At home, things aren’t going well either—he’s no longer able to connect with his partner, who eventually leaves him. Despite being a model worker, he is fired by the company. This marks his realization that he had been deeply alienated.

After being re-hired thanks to the solidarity of his fellow workers, with whom he reconciles, he starts telling anecdotes at work. He shares that he dreamt he was breaking through the walls of paradise—with his comrades.

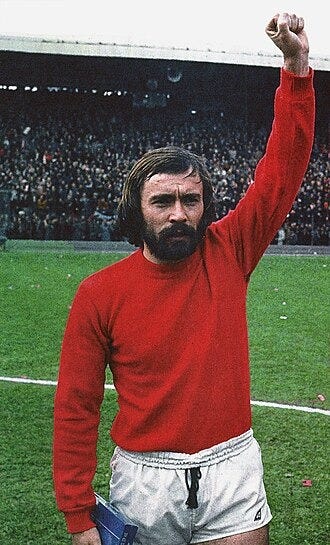

In football at the time, there was a player who also belonged to the working class—a politically committed footballer close to the factory workers’ struggles: Paolo Sollier. Sollier was an oddity, because in those years, football (calcio) was often snubbed by left-wing intellectuals, seen as a moment of escapism and passivity. On the other hand, it was extremely rare to see a Serie A player openly endorsing leftist ideals, taking the workers’ side, and raising his fist on the pitch to signal his proletarian roots.

Today we tell the story of Paolo Sollier.

Workers' Vanguard ⚒️

Before becoming a symbol of militant football, Sollier was a young factory worker (FIAT Mirafiori) and a politicized student in 1970s Turin—a hotbed of trade union struggles and the extraparlamentare (extra-parliamentary) movement. He grew up in the working-class neighborhood of Vanchiglietta, surrounded by factories and mimeographs. He joined Avanguardia Operaia (Workers' Vanguard), one of the most active revolutionary leftist organizations in post-1968 Italy. Before joining them, he had also collaborated with Catholic-inspired solidarity groups like Emmaus and Mani Tese.

Founded in Milan in 1968, Avanguardia Operaia emerged from grassroots committees and student movements. Characterized by its strong working-class roots, the organization distanced itself from Stalinism and leaned toward Leninism and democratic centralism. This experience eventually gave birth to a new political party: Democrazia Proletaria (Proletarian Democracy).

The group saw class conflict and the mass mobilization of workers as the only path to overturn the status quo. Sollier embraced these ideals with consistency—participating in assemblies, distributing flyers, discussing in party sections, and engaging in a grounded but non-dogmatic militancy. Workers' Vanguard gave him a political language, a framework to interpret society, and a community. Paolo never separated the pitch from the protest, the athletic performance from the political procession.

The Football Career ⚽

In footballing terms, Paolo Sollier began his career between the late ’60s and early ’70s in Serie C, the third tier of Italian football. He was a solid midfielder, known for his grit, heart, and endurance. After an impressive 1973–74 season with Pro Vercelli, Sollier caught the eye of Ilario Castagner, who brought him to Perugia in Serie B. There, he had a standout season that ended in promotion to Serie A. The 1975–76 season marked the peak of his professional career.

Before matches, he became famous for raising his fist toward the Perugia fans—who shared his leftist leanings. This gesture outraged many rival fanbases, especially those of Lazio, a club traditionally associated with the far right. Sollier explained that the salute was a way of signaling that he hadn't forgotten his roots and to show his friends that professional football hadn’t changed him. It was a symbol of identity.

In 1976, he published his autobiography Calci, Sputi e Colpi di Testa (Kicks, Spits & Headers), where he wrote about his political commitment and offered a unique perspective on football. The book earned him a fine from the FIGC (Italian Football Federation).

After leaving Perugia, Sollier continued his career with Rimini, Pro Vercelli (again), Biellese, and Cossatese, retiring in the 1984–85 season.

NO TAV 🚫

The NO TAV movement was born in the early ’90s among the inhabitants of the Susa Valley (province of Turin), in opposition to the Turin–Lyon high-speed rail line. Protesters viewed it as a massive waste of public funds and a source of environmental devastation. Over the years, the movement organized numerous demonstrations. Though the NO TAV movement identifies as pacifist, tensions with law enforcement have frequently erupted—most notably during the 2005 permanent encampment in Venaus, when thousands occupied the construction site, forcing authorities to relocate the project.

Paolo Sollier, born in Chiomonte, in the Susa Valley, became a staunch supporter of the NO TAV initiative. He described the seizure of Venaus as a symbolic and concrete victory, a moment of collective identity. In 2011, work resumed in the Clarea Valley (still within Chiomonte), leading to renewed protests. Over the years, the NO TAV movement has demonstrated an extraordinary level of civic participation and collective awareness.

Beyond this, after leaving football, Paolo Sollier ran a bookstore, became a journalist and football coach, and eventually joined the political party Potere al Popolo! (Power to the People!).

Despite having retired from football, he never stopped fighting outside the pitch.

This is the link if you want to purchase his autobiography: https://www.amazon.it/Kicks-Spits-Headers-Autobiographical-Reflections/dp/1570273936

If you liked the article, please subscribe to reach 100 subscriptions.

For some reason, he reminds me of George Best. But seriously, his autobiography is probably a good read. My grandfather was from Turin. Great article.